Here’s the sticky wicket about blogging.

Often you can’t write about things in real time because to do so could affect the course of events, in ways you can’t foresee, so sometimes you have to just sit on things. Voila, the case of the tanker engine parts and the Bushey tankers Ked and Mary Whalen. The story from September through February will now come out in installments. Yes, I kept all emails and good notes. The posts are mostly all written.

Tanker engine parts - The first week of September, 2008:

Thanks to a tip from Bernie Ente, I learned that another Bushey tanker was being scrapped oh so far away in Seattle, and I made a play for parts. Engine parts, davits, interior cabinetry and brass fittings. Several Whalen cabins were gutted when she was in Erie Basin being an office and one day, we’d like to restore bunks, hanging lockers n such. Right now we need those spaces for offices, but once we have a base ashore, we can get that stuff off the boat and restore more.

Thanks to a tip from Bernie Ente, I learned that another Bushey tanker was being scrapped oh so far away in Seattle, and I made a play for parts. Engine parts, davits, interior cabinetry and brass fittings. Several Whalen cabins were gutted when she was in Erie Basin being an office and one day, we’d like to restore bunks, hanging lockers n such. Right now we need those spaces for offices, but once we have a base ashore, we can get that stuff off the boat and restore more.

Anyway, first answer out of Stabbert Shipyard in Seattle was a lot of silence.

I looked at their website and saw that one line of their business was turning old workboats into luxury yachts. Was this what they would do with Ked, I wondered, and so wouldn’t want to give stuff away? Were they really scrapping the Ked? If so, it certainly would seem preposterous to a scrapper to get a call from across the continent, from a non-profit, and I suspect, from a woman, looking for parts to save an old tanker. No one saves tankers! Tugs maybe; yachts surely, but tankers don’t have Enthusiast Societies, yet.

I looked at their website and saw that one line of their business was turning old workboats into luxury yachts. Was this what they would do with Ked, I wondered, and so wouldn’t want to give stuff away? Were they really scrapping the Ked? If so, it certainly would seem preposterous to a scrapper to get a call from across the continent, from a non-profit, and I suspect, from a woman, looking for parts to save an old tanker. No one saves tankers! Tugs maybe; yachts surely, but tankers don’t have Enthusiast Societies, yet.

What to do? Here my old skills as a journalist, a foreign correspondent of the pre-digital era were useful. I did most of my work overseas in a career that ran from opening of Berlin Wall to 9/11 in countries that often didn’t have decent phone systems (or had phones systems with the government listening in). The way you got information was social. You saved every name and number you ever got, you horded them, you kept them in handwritten notebooks; and these names and numbers were exchanged with select (friendly) journalists coming and going to the same countries. This is a segue to a little rant of mine: I’ve noticed that 20-somethings who come to work at PortSide are conversant with web and digital connections but less good at reaching people to solve a problem. Once they’ve googled or filled out the web contact form, they’re done; and when that isn’t working/doesn’t net the solution, it’s often hard to get them to get on the phone, to reach out and touch someone; and most to the point, they don’t seem good at recruiting a person to the cause to help solve the problem at hand. It makes me appreciate being middle-aged and having experienced the world before email, web, and customer service in India.

But back to the Ked parts... I began reaching out. When PortSide was creating its business plan, a Capt. Kris Lindberg out of Seattle had worked for us. He did a raft of things and headed all the market research on the charter and excursion boats in NYC and determined which would be interested in coming to our proposed Maritime Hub. He was getting a Masters in planning at the time and thinking desk job after years of running boats from Seattle to Alaska. After graduating from NYU in 2005, he returned to Seattle. I called.

Turns out Kris knew the Ked well. He had not got a desk job after all and was doing environmental ops for Global Diving & Salvage Inc., and had been on the Ked just months before. Global did the abatement work on the Ked, and had bid on the scrapping job and lost to Stabbert.

I called K-Sea in NY, knowing they had bought a Seattle tugboat company. Could their Seattle folks could see if the Ked was still afloat… Answer: yes.

I called the Washington State Dept of Natural Resources, Derelict Vessel Division to see if they could find a way to help. I had no idea what their contract to Stabbert allowed or mandated, but surely scrappers worked with eye on the clock and wanted no delays. Could they facilitate? Melissa Montgomery said “Yes, we’d love to.”

I got my brother Antonio Salguero of Coastwise Marine Design, on the phone. He’s worked a range of marine jobs near Seattle (fishing boats in Alaska, shipwright at Port Townsend’s shipwright’s co-op, freelance yacht designer and shipwright). Could he come down from Port Townsend to Seattle to visit the Ked and assess? Yes.

On the eastern front, I started calling folks to learn more about the Whalen’s engine, what had failed, what was fixable, what other Bushey tankers had for engines as a way to determine what this thing in the Ked might be, even what this Ked was originally called to learn more about her. I asked about alternative sources for parts because schlepping things from Seattle looked expensive on the transpo alone… and the logistics of cross-continent research were going to be challenging.

All that hadn’t been done earlier, because, honestly, the planning team did not see the engine as an immediate priority. The Whalen can deliver a lot of programming as a dead ship. We came to her as the cheap alternative to a spud barge, a means to a docking end, making her go was not the plan. Admittedly, our thinking was evolving since we learned some things during ship tours.

What we learned was that the engine room was the 2nd most popular place on the boat. Galley first, engine room second. The wheelhouse, to our surprise, was definitely third. We had considered yanking out the whole old engine (down the road) to give us more space, and then we listened to the public. As Tim Ventimiglia, our museum designer, put it “I thought the boat and engine room would really appeal to middle-aged men, but that is not what is happening.”

I remember the day the Whalen’s engine room cured a woman. I was leading a tour of 15. As we approached the engine room stairs, a woman said “’oh no.”

“What’s the matter,” I asked?

“I’m claustrophic.”

I said “here’s what we’ll do. I’ll hold the group back, you go down there, and if you feel uncomfortable, you can rocket right back up those stairs, and no one will be in your way.”

She went down the stairs. Silence.

“Are you all right?” I yelled.

Then came the answer “WOW.”

I told the group to stay on the fidley and went down. “You OK?”

“This is amazing.” And there she stayed, so excited by the engine that she wasn’t claustrophic and was able to have a crowd of 14 join her for a 20 minute stay down there.

So we learned over tours large and small that because the engine room captivated, it created a way to discuss mechanical and infrastructure topics you would think were too dry for the public: the dated peculiarities of a bell boat system and a direct-reversing engine and what that meant for ship staffing, shaft generators and how the ship created and stored its own power. Even the marine composting toilet system interested people. Not to mention the thrills the engine room brings to kids. For them, it is the best of cave, tree fort and space ship.

The looming, antique lump of the engine had a powerful voice; and so, when engine parts seemed available, I thought we should try for them. They might not get installed for years, but if we started looking for them years from now, they surely wouldn’t exist. With the price of scrap steel high, old boats were being scrapped pell mell; and old marine businesses all over the country were being pushed out by gentrification, so repair places with old parts were on the wane.

And so, as inconvenient as the timing of the Ked’s demise was for PortSide’s autumn plans, I went for it and redoubled my efforts on the phone.

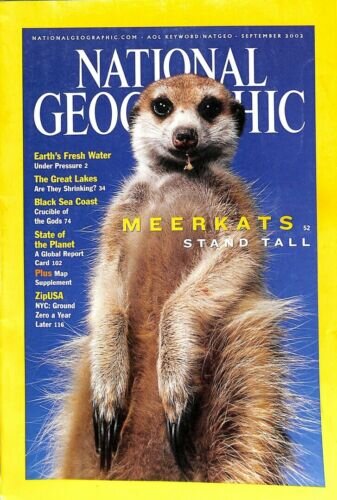

When Fairway needed a rezoning to get a supermarket in an m-zone on the waterfront, they were asked “why do you need to be on the waterfront” and they gave the answer “because we will service the working waterfront” and they talked about tugboats coming in to shop. I had supplied the information that tugboats would flock to a waterside supermarket since it had become so hard to get provisions due to the decline of finger piers near neighborhoods. I learned that while doing my National Geographic

project on tugboats in NYC. The PortSide business plan followed up on that knowledge and surveyed the local towing industry about how much they spend on boat grub a year ($7.MM) and whether they wanted to shop at Fairway (yes) and why. We concluded that $1.5MM of business wants to shop at Fairway. PortSide was going to position shopping tugboats as an attraction, much as they are in Fells Point, Baltimore, and build our maritime museum concepts around visiting real boats doing real things.